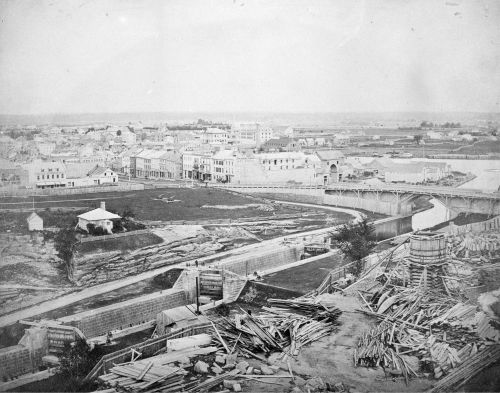

Chosen as the capital of the united Province of Canada in 1857, Ottawa enters a phase of rapid development. Construction of the future parliament and government buildings accelerates the growth of commerce and the timber industry. From 1851 to 1861, the population grows from 7,760 to 14,669 residents. Ten years later it rises to 21,545 – a total increase of 178%. Growth within the Francophone group – from 2,056 in 1851 to 7,214 in 1871, a 200% surge – is greater than the increase of the total population. French Canadians, among them civil servants coming to work in the new public service, represent a third of Ottawa’s population. Their numbers continue to rise as government activity grows, reaching 68,459 in 1961. However, they then comprise only a quarter of Ottawa’s population.

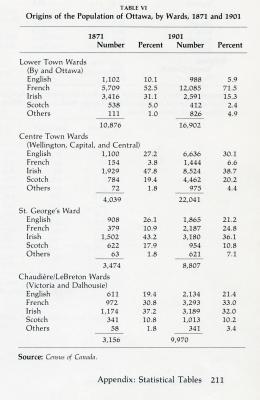

In the aftermath of Confederation, Ottawa is divided socially and ethnically, as are many other North American cities. The English and Scottish population is fairly well distributed among the different districts of the city, while four-fifths of French Canadians live in Lowertown, a neighbourhood where they have been the majority since the founding of Bytown. Many Francophones also live west of Parliament Hill on the LeBreton Flats, where they are employed by J.R. Booth, the world’s largest lumber producer at that time. As for the Irish, they also dwell in Lowertown, which accommodates the largest contingent of this group. In addition, the Irish forms a significant portion of the population of Centre Town, gathering in the area that extends south of Parliament Hill. Other groups (Germans, Italians, etc.) do not emerge in the ethnic landscape until the turn of the 20th century.

A division corresponding to social class is superimposed on these ethnic divides. Historian John Taylor notes, based on 1871 data, that “in the lower and middle income ranges, the civil service [is] located according to cultural background: the Roman Catholics, French and Irish, largely in Lower Town, and the Protestants in Upper Town.”1 Individuals in higher income brackets are well represented in Sandy Hill (St. George’s Ward), a neighbourhood where development is stimulated by the growth of the public service. Segregation along religious or ethnic lines is not evident there, however. It does not appear to affect the upper levels of the social pyramid.

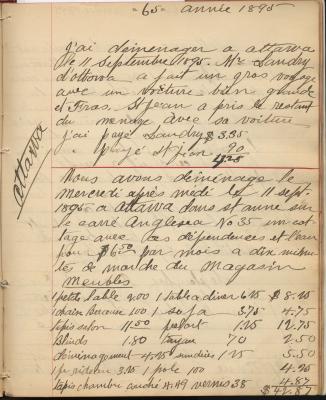

Not all Ottawa populations enjoy the same quality of life. Taylor reports troubling data in this regard. In 1885, 43% of Ottawa’s mortalities occur among French-speaking Canadians, who account for only 34.2% of the city’s population at the time, according to the census. The Lowertown By district, where only 18.1% of Ottawa’s population lives, records the city’s highest mortality rates by far: 37.9%.2 Many children die in infancy. David Emile Neveu, for example, passes away on September 14, 1895, after three months of illness. With this death, the father, Jean-Baptiste, a store clerk who just moved into the neighbourhood, loses the third of his seven children.

1 John H. Taylor, Ottawa, an Illustrated History, Toronto, James Lorimer & Company Publishers and the Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1986, p. 84.

2 Ibid., p. 212.

Rideau Street, seen from Parliament Hill, where the construction of East Block (United Province of Canada Parliament) begins, [ca. 1861]. Photo: Samuel McLaughlin.

Source : Library and Archives Canada, Historical photographs of individuals and groups, events and activities from across Canada collection [graphic material], (R8239-0-9-E), C-000610.