The driving force behind the development of Sandy Hill is a political figure from Lower Canada and native of Québec: Louis-Théodore Besserer. Pursued by the British government after the rebellion of 1838, he seeks refuge in Bytown in 1845, where he settles on a large tract of land he purchased a few years earlier, on the slope bordering Rideau Street to the south. A shrewd businessman, he subdivides the land into numerous lots, including a site reserved for a church and a school to attract families. He donates six lots on Wilbrod Street to establish the College of Bytown, which later becomes the University of Ottawa. The institution still occupies this location today. Besserer also has several streets laid out, one of which still bears his name. He apparently makes a fortune and becomes quickly anglicized; he identifies increasingly with the English-speaking population.

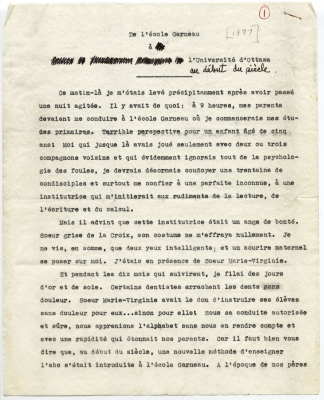

With the exception of a few houses, including one he builds in 1844, Sandy Hill remains relatively uninhabited until the establishment of government in Ottawa in 1857 and the ensuing rapid growth. Civil servants then commit to the neighbourhood, which develops into one of the most prosperous and prestigious areas of the capital. Illustrious Ottawans, including Séraphin Marion, grow up in Sandy Hill, study at the Garneau school, and attend the Sacré-Coeur parish.

In addition to affluent Francophones, Sandy Hill attracts Anglophones of Irish, English and especially Scottish origin. The Victorian houses on Daly Street reflect this Anglo-Saxon heritage. The neighbourhood cannot, however, withstand the onslaught of densification, which, during the post-war period, sees multifamily buildings spring up on the same streets. The expansion of the University of Ottawa also changes the landscape. The neighbourhood, which becomes occupied by embassies, remains a centre of French life in the capital, but its population changes dramatically.

Daniel Poliquin depicts Sandy Hill’s particular character in Visions de Jude (Visions of Jude), published in 1990 and reissued in 2000 under the title La Côte de Sable. The novel is less about the neighbourhood itself, and more about the rootless existence it produces, a reflection of the city as a whole:

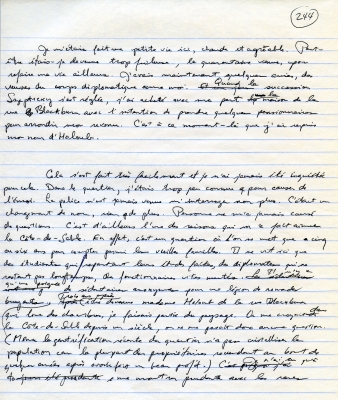

… Living here for four or five years makes you a lifetime resident. The area is a haven for students, who move on as soon as they graduate, for diplomats, who never live anywhere for long, and for civil servants, who pass through on their way up (or down) the social ladder. Among so many nomadic tribes, there are only a handful of faceless squatters, and within three years of becoming Madame Holoub on Blackburn, who rented rooms and was affectionately called Madame Elizabeth by her boarders, I had become part of the landscape… Even the recent gentrification of the area hasn’t created a relay coherent community, since most of the new owners merely give their houses a quick facelift and then resell them a year or two later when the prices go up.1

1 Daniel Poliquin, Visions of Jude, Vancouver and Toronto, Douglas & McIntyre, translated by Wayne Grady, 1992, p. 143-144.

Sandy Hill, house facade, Daly Street, Ottawa, July 8, 1975. Photo: François Roy, Le Droit.

Source : University of Ottawa, CRCCF, Fonds Le Droit (C71), Ph92-1064-20771COT-5.